“April 30, 1945” Tears, Chaos, Relief : True Stories from The Day the Tyrant Fell

The Day the War Shifted Its Weight

On April 30, 1945, Adolf Hitler killed himself in his bunker beneath the crumbling Reich Chancellery in Berlin. The war did not end that day — but something else did. A grip loosened. A breath held too long was finally released. And across Europe, in whispered rumors and radio crackles, the world began to understand: the tyrant was dead.

But for those who lived through that moment, the news came not as headlines — it came as shouts in the streets, tears on balconies, and the sound of boots moving in a different direction.

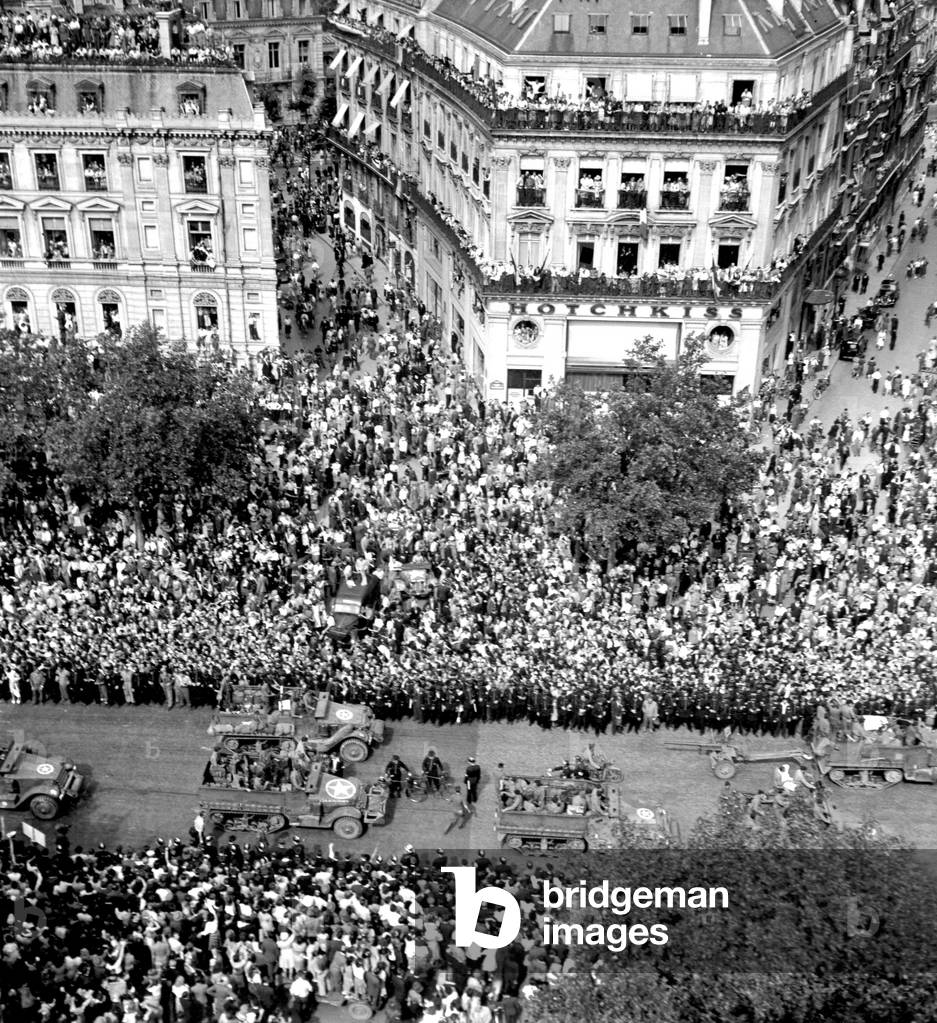

A Woman on the Balcony in Paris

In a building along one of Paris’s wide avenues, a woman stood on her balcony with a radio pressed to her chest. The voice coming through the static was telling her that De Gaulle was returning, that the Allies were pushing the Germans out, and that Paris — her Paris — might be free again.

Her granddaughter would one day tell the story like this:

“She stood there listening, watching. And then she saw them — Allied soldiers sweeping down the avenue. She didn’t wait. She ran down barefoot and into the street, despite the gunfire still cracking in the distance. An American soldier tackled her back into the doorway and scolded her. She didn’t understand a word. But she cried and cried, because she was just so happy to see him.”

She still tells the story, tears in her eyes, not knowing if she was weeping for joy or for everything that had been lost.

The Madness in the Bunker

image credits: Alamy.

Meanwhile, hundreds of miles away and a world apart, Berlin was crumbling.

Inside the Führerbunker, Hitler married Eva Braun in a brief ceremony and gave out cyanide capsules as wedding favors. Staff were burning documents. Guards were ordered to shoot their own dogs.

Then, on April 30, he shot himself. Braun took poison.

By May 1, the world knew — through an awkward, delayed announcement made by Admiral Dönitz on German radio.

The words were carefully chosen:

“Our Führer, Adolf Hitler, has fallen… Fighting to his last breath.”

For many, the moment didn’t feel real. But something shifted. It was as if the air had changed.

In the Netherlands: Hunger, Gratitude, and the Sky

In Nazi-occupied Netherlands, families were starving. The winter of 1944–45 had become known as the Hunger Winter. Children ate tulip bulbs. Bread was a rumor.

In the spring of 1945, an extraordinary agreement was reached: a temporary ceasefire to allow Allied bombers to drop food supplies over Dutch territory. There weren’t enough parachutes — so they dropped sacks from low-flying planes, trusting the people to catch them.

A man who had been a boy in those days later recalled:

“We saw bombers, but this time they weren’t dropping death. They were dropping bread. My mother cried harder than I’d ever seen.”

You’d understand why — if you knew that years earlier, she had survived the worst of the camps. The one the Red Army found when they walked into Auschwitz.

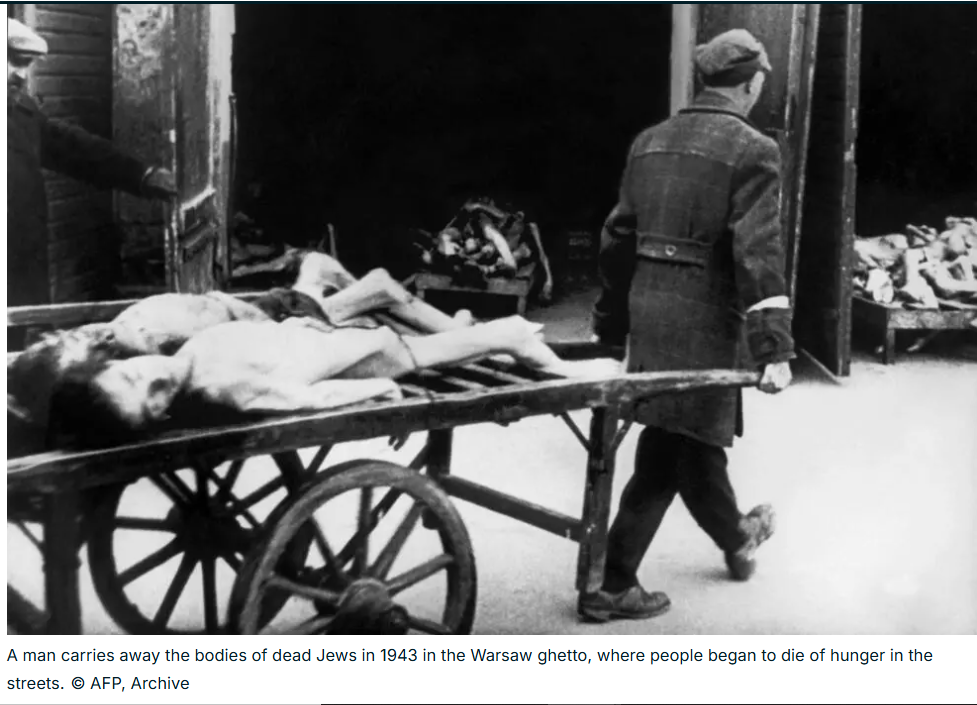

“The actual camp appeared like an untidy slaughterhouse. A pungent smell hung heavily in the air… The further we walked into the site, the stronger the smell of burnt flesh became, and dirty-black ash rained down on us from the heavens, darkening the snow…”

These were the words of Nikolai Politanow, one of the first Red Army soldiers to enter Auschwitz. His account was never meant for books or lectures — it was simply what he saw, and what he never forgot.

👉 Read the full account here.The Netherlands was officially liberated in early May — days after Hitler’s death — but for many, the shift began in that strange moment: food falling from the sky.

On a Rooftop in Poland

In Eastern Europe, liberation did not come with the same joy. For many Poles, the retreat of the Nazis meant the arrival of Soviet troops. After years of one brutal occupation, another loomed.

One woman, a grandmother now, once told her granddaughter what she did when the Red Army approached:

“I climbed to the roof and tied myself to a chimney. I thought if I couldn’t run, maybe they’d leave me alone. I didn’t want to be raped. Or killed. I wanted to disappear.”

That’s the other side of the day Hitler died: for some, it meant not safety — but the start of another kind of fear.

Two Friends and a Fateful Escape

Then there’s the story of two friends — prisoners in a camp — who could no longer endure the torture. One night, they made a pact: they would escape or die trying.

They walked 120 miles by foot, barefoot, under the cover of night. It took them five weeks to reach safety. When they arrived, they found out the camp had been liberated just two days after they escaped. Hitler had died four days later.

What they must have felt — grief at the suffering they endured, relief to be free, and the quiet devastation of how close they were to salvation — is hard to describe. But it lingers in the story.

In a Small Dutch Town: A Chocolate Tank

Liberation brought surreal moments, too. One Canadian teacher remembered how, as a boy in the Netherlands, he saw soldiers arriving with tanks.

“One soldier stuck out of a tank was Black — the first Black man I had ever seen. That day they were handing out more chocolate than I had ever seen. My little brain put it together: that tank must be full of chocolate. And that man must be made of it.”

It was innocent. It was strange. And it stuck with him for a lifetime.

When the World Stopped Spinning

April 30 was not a neat ending. In the days that followed, soldiers still died. Cities were still occupied. The Holocaust was still being uncovered.

But the symbolism mattered. Hitler’s death meant the myth of Nazi invincibility had shattered. What followed was surrender, trials, rebuilding — and remembering.

It meant stories could begin to be told. It meant survivors could step forward. And it meant people who had tied themselves to chimneys, or run into gunfire out of joy, or carried bread from the sky — could finally say: “It’s over.”

What He Left Behind

Hitler left behind a broken Europe, a trail of death stretching from the Atlantic to the Volga, and generations shaped by what they endured or lost. He left behind mass graves and ruined cities, empty chairs and silent radios.

But he also left behind defiance.

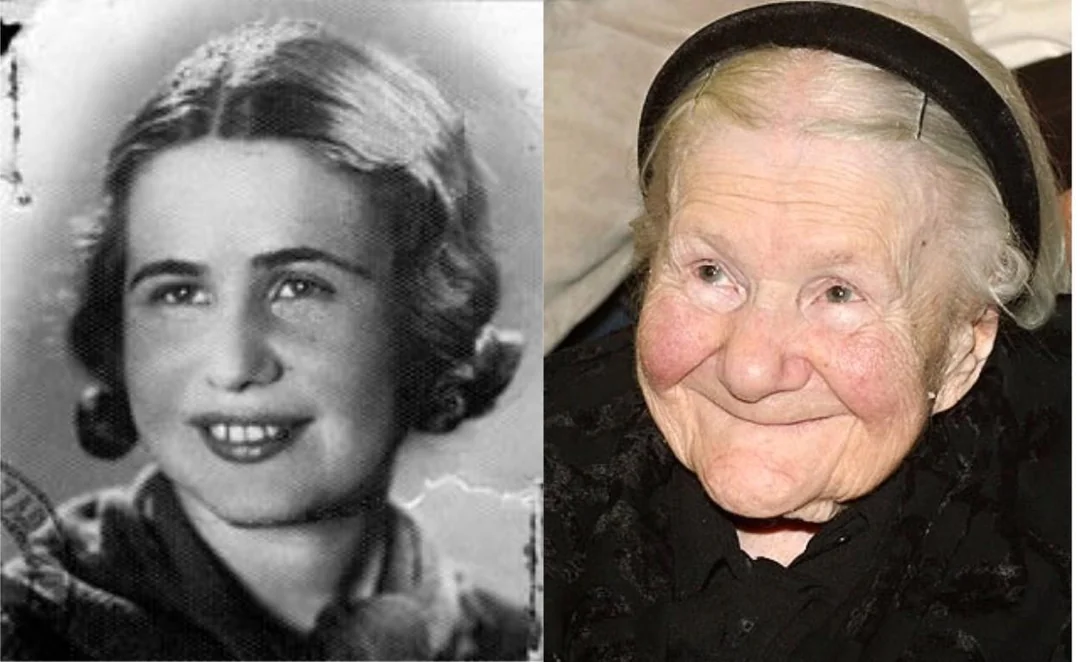

- In the courage of a social worker like Irena Sendler, who smuggled 2,500 Jewish children out of the Warsaw Ghetto.

- In the Polish and Dutch families who risked their lives to hide strangers.

- In the children who survived, and who now — in their 90s — still tell the stories.

The Tyrant Died, But the Stories Lived

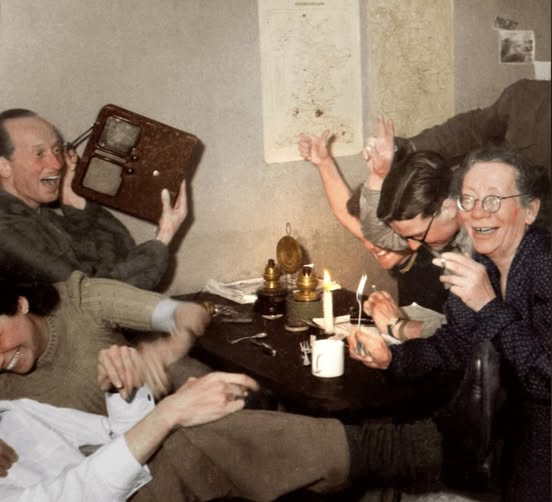

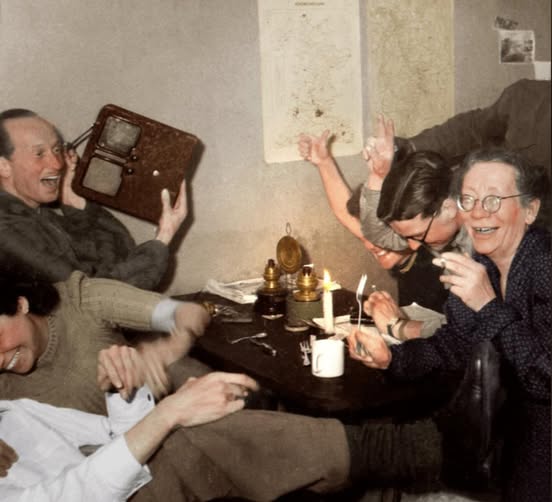

On that day, many did not cheer. They sat still. They wept. They held hands in quiet kitchens. They listened to radios in disbelief. Some returned to graves they hadn’t been able to visit. Others simply stared at the sky.

The tyrant had died. But not before shaping — and scarring — the world.

And so the world began to rebuild. From balconies. From rooftops. From mattresses used as landing pads. From the ashes and from the memories.

They stitched their futures from scraps.

They loved again.

They named children.

They grew old.

They lived.