Caddo Lake’s Cool History: Oil Rigs, Swamps, and the Secrets Beneath the Cypress

Sometimes, a video opens a door.

A few days ago, Jerry Maune , one of the followers on my history page, tagged me in a comment. It was on a short clip from @firstcastcabin — what seemed to be a wise man, talking calmly beside some quiet water, pointing out a spillway. At first glance, nothing seemed remarkable. But by the end, I was leaning in. Because what he was explaining wasn’t just about a lake. It was about a problem no one knew how to solve… until they did.

That lake was Caddo Lake, sitting right between Texas and Louisiana. And what happened there over a century ago is part mystery, part marvel — with just the right dose of swampy, Southern grit.

Let’s take a walk into it. Slowly. Like kids crossing a muddy ditch in school shoes.

A Lake Born by Accident — and Logs

Caddo Lake didn’t start out as a lake. Around the early 1800s, something massive happened upstream on the Red River. A logjam formed — not your backyard branch pile, but a truly colossal wall of wood and debris. It stretched for over 100 miles.

People called it the Great Raft. It blocked the river’s flow so severely that the water had nowhere to go… except out. The surrounding flatlands flooded over time, and nature, without asking anyone’s permission, created a vast, shallow, tangled swamp.

Eventually, this became Caddo Lake — a ghostly maze of water, moss-draped cypress trees, and slow, quiet channels. And for decades, it stayed just that: a wild, misty backwater. Good for fishing, maybe. But hard to tame.

Until someone smelled oil.

The Swamp That Hid a Fortune

By the early 1900s, geologists were saying something wild: there was oil beneath Caddo Lake. Not just traces, but real pools of it, trapped in faulted rock deep below the murky bottom.

That’s when things got interesting. Because the oil wasn’t under dry land — it was under swamp.

Now, if you were around in the late ’70s or early ’80s, you might remember the feeling of trying to ride a banana-seat bike across your uncle’s overwatered lawn. The back tire would sink. You’d keep pedaling, digging a hole, going nowhere. That was basically the problem the early oilmen faced — but with drilling rigs instead of bikes.

You couldn’t bring heavy equipment into a swamp without it sinking. Roads were useless. Platforms collapsed. The oil was sitting just out of reach, laughing.

But instead of giving up, they got creative.

The Spillway Trick

Here’s where the story takes a clever turn .

In 1914, engineers came up with a strange but smart idea: instead of trying to dry the swamp, what if they flooded it even more?

They built a spillway — basically a dam — at the lake’s outlet. It raised the water level to a consistent depth (about 168.5 feet above sea level). This did two things:

- Turned shallow, sticky swamps into navigable lake

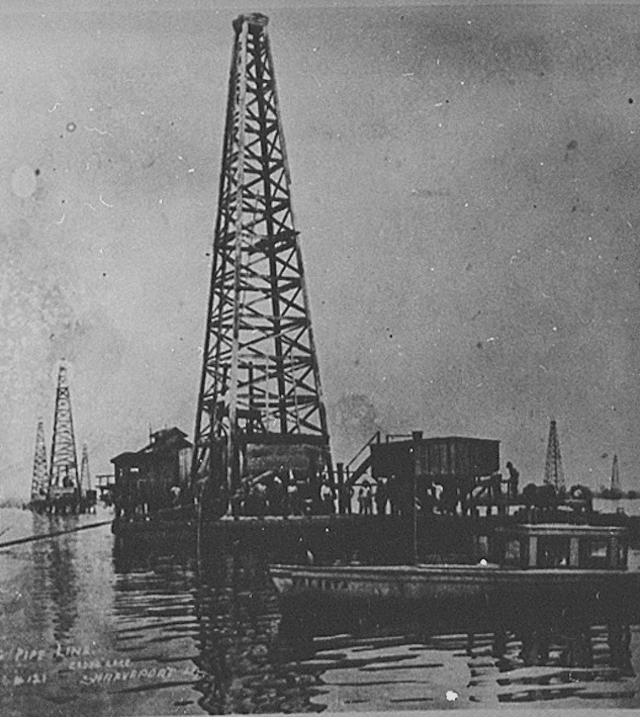

- Allowed floating drilling rigs and barges to move in and do their work

And just like that, oil wells began popping up right on the water. In fact, Caddo Lake became home to the world’s first over-water oil well. A piece of quiet backcountry had become a floating oil field.

That’s not just clever. That’s the kind of story you half-expect to see in a dusty library book, the kind you only pick up because the cover has a gator on it.

The Drawbridge, the Towns, and the Boats

To connect the dots — and the people — a drawbridge was built in 1914 between Port Caddo and Oil City. It lifted to let tankers and supply boats through, and lowered to carry cars, wagons, and workers.

The thing still stands today. A steel-boned memory of a time when engineers wore vests, not vests with logos.

Back then, this whole region was booming. Oil rigs hummed. Barges creaked through the water. New towns sprouted up, most of them with the kind of names that sounded made up: Rodessa, Oil City, Trees.

Some of those towns flourished. Some faded. But the energy of that era — the risk, the sweat, the sheer belief that you could figure things out — lingers.

Other Voices, Other Stories

Over the past few days, I’ve come across more pieces of this history. People who grew up near Caddo Lake — or whose parents did — shared bits I never would’ve known:

- One man said his grandfather worked a tugboat out there during the 1930s. “All night, lanterns on the water,” he wrote. “You’d see them drift like stars.”

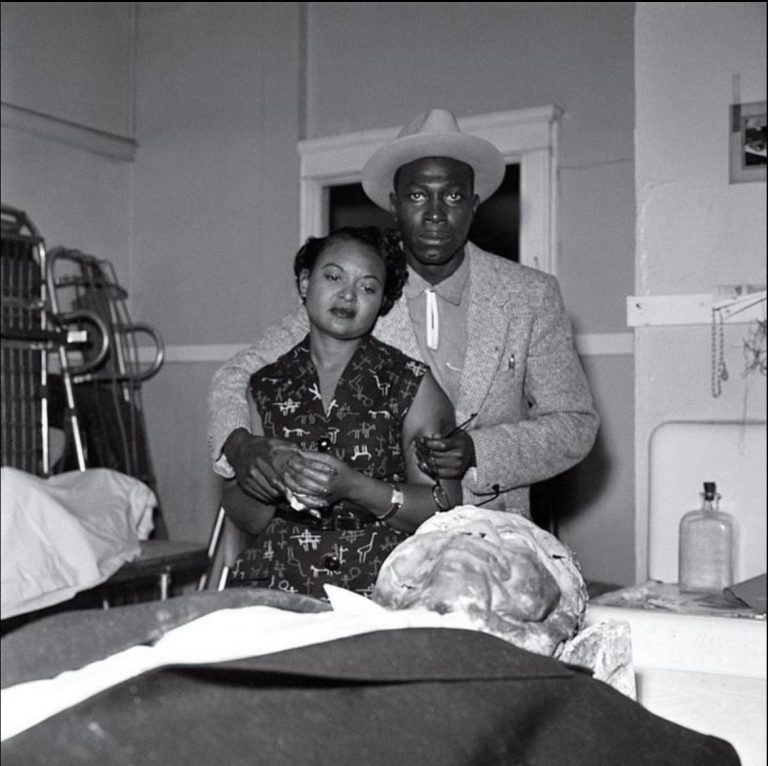

- A woman recalled hearing stories of fires that lit the lake sky red. Oil fires — dangerous, fast. But oddly beautiful in memory.

These stories aren’t mine, but they feel real. And if you’re from the South — or have family from there — maybe you’ve heard echoes of them too.

The Caddo People, and the Name We Still Use

Long before oil, before bridges or barges, this place was home to the Caddo Nation — a group of Native American tribes who lived across East Texas and parts of Louisiana. The lake is named after them.

They farmed, fished, and lived in this landscape when it was still raw and unpredictable. Their story is quieter in today’s history books, but it’s not gone. And it’s worth remembering that the land holds more than one past at a time.

After the Boom: A Lake Reborn

By the mid-20th century, the oil boom slowed. Rigs disappeared. Refineries shut down. Nature, patient as always, began to reclaim the shoreline.

Today, Caddo Lake is a protected reserve — a swamp again, but this time loved for it. It’s a home to birds, alligators, cypress trees, and still-water reflections.

People come to paddle quietly, to fish, to photograph Spanish moss in golden light. The oil is still there, but no one’s in a rush to dig it out anymore.

A Final Note from the Back Row

When I was in school in the early ’80s, we had a substitute teacher once who showed us slides from her trip to Louisiana. Swamp photos, mostly. One kid whispered that alligators could smell chewing gum. I remember watching the images, feeling bored, but also weirdly drawn in.

I think about that now. Back then, I didn’t know those swamps were full of stories — of oil spills, of clever dams, of Native villages, of barges with lanterns. Places like Caddo Lake look sleepy. But they’re not.

Sometimes, a quiet lake holds louder history than a city block.

And sometimes, all it takes to find it is a comment under a video. thank you again Jerry Maune for tagging me to discover this great piece of history.