Chiune Sugihara — The Japanese Diplomat Who Wrote Visas for Hope

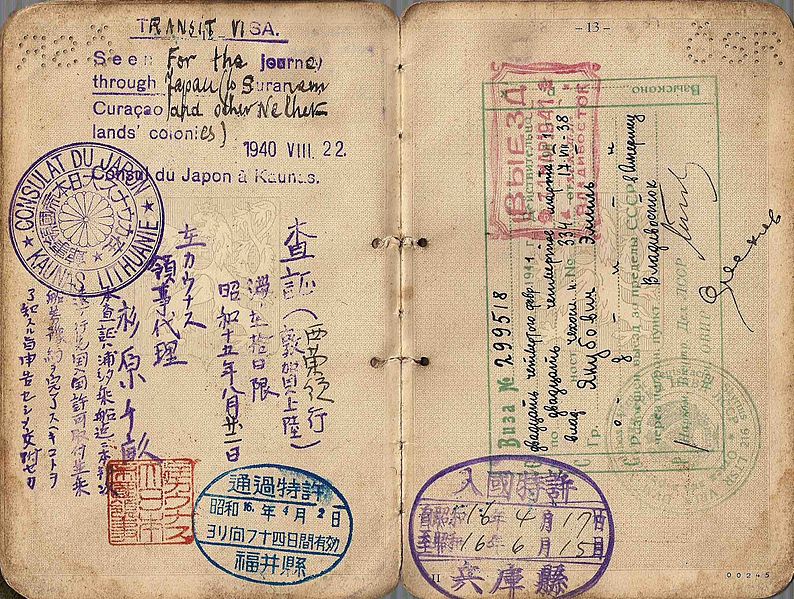

In the summer of 1940, in a small office tucked inside a Japanese consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania, a man sat at his desk, writing by hand. Page after page. Hour after hour. His wife brought him meals he barely touched. His signature became a lifeline.

That man was Chiune Sugihara. And the documents he signed were not ordinary forms — they were exit visas.

Visas that allowed thousands of Jewish refugees, many of them desperate and already displaced, to pass through Japan and escape the tightening grip of Nazi Germany.

He wasn’t a resistance fighter. He didn’t sneak people over borders in the dead of night. He simply used what he had — a diplomatic title, a pen, and a moral compass that refused to bend.

The Road to Lithuania

Sugihara was born in 1900 in Japan. He was educated, thoughtful, fluent in several languages, and trained in diplomacy and foreign affairs.

By 1939, he was posted as vice-consul in Kaunas, where the political situation was growing more desperate by the day. Hitler’s forces had pushed westward, Stalin’s troops had moved in from the east, and refugees — especially Jews — were flooding into Lithuania with nowhere to go.

They lined up outside embassies and consulates, clutching documents, whispering rumors, and begging for help. Most doors were closed.

But Sugihara listened.

Visas Against Orders

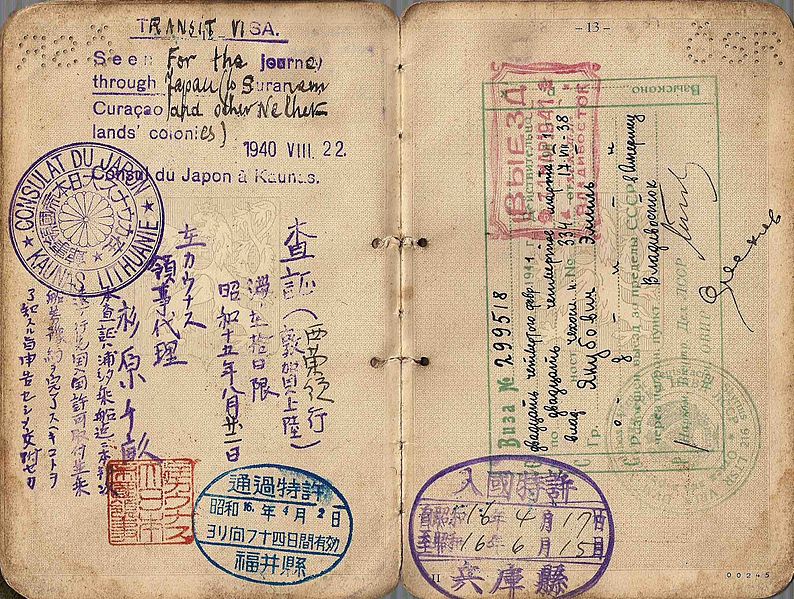

It started with a knock. And then another. Soon, crowds of Jewish families were gathering outside the Japanese consulate. They needed transit visas through Japan — not for final refuge, but as a stepping stone to freedom elsewhere.

Sugihara wired his government in Tokyo three times, asking permission to issue the visas. Each time, the answer came back: no.

He was told to follow protocol. Only people with proper documentation and final destinations could be granted passage. The refugees had neither.

So Sugihara made his choice.

He wrote the visas anyway.

By hand.

Day after day, he sat at his desk writing transit papers for men, women, and children — including many who had no passports, no money, and no other way out.

He signed as many as he could each day, reportedly working 18–20 hours at a time.

When he ran out of official forms, he wrote on plain paper. When the consulate was ordered to close, he took the documents to his hotel. On the morning he left Lithuania, he was still signing visas from the train platform and throwing them through the window to people who ran beside the train, holding onto hope.

His final act, just before the train pulled away, was to hand the visa stamp to a refugee — in case more were needed.

The Cost of Conscience

Sugihara knew his actions might have consequences. He was disobeying direct orders, defying a government that expected strict compliance, especially in wartime.

After the war, his career quietly ended. He was forced to resign from Japan’s foreign service in 1947, and though the official reason was downsizing, many believe it was linked to his defiance in Lithuania.

He lived modestly for the rest of his life. Worked various jobs, including as a translator and a representative for a trading company. He rarely spoke about what he had done.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that people began to uncover the scope of his actions. Survivors started searching for him. One man, Nathan Lewin, had carried a visa with Sugihara’s signature as a child — and wanted to thank the man who had saved his life.

In 1984, Sugihara was named “Righteous Among the Nations” by Yad Vashem in Israel. He was invited to visit, met some of the families he had saved, and was overwhelmed by the gratitude that had quietly grown in the shadows of history.

The Numbers — and the Lives

Historians estimate that Sugihara issued between 2,000 and 3,500 visas, which ultimately saved the lives of over 6,000 Jews — accounting for families and children who were able to travel together.

Some made their way through Japan to Shanghai. Others reached safety in the U.S., Canada, Australia, or Palestine.

What began with a few lines of ink on a page became a family tree of survivors — generations who owe their lives to one man’s quiet refusal to look away.

Among those saved were rabbis, musicians, scholars, and everyday people who would go on to build communities, raise families, and carry stories that would otherwise have ended in 1940.

A Gentle Legacy

Chiune Sugihara died in 1986, at the age of 86.

Only in the final years of his life did Japan begin to publicly acknowledge his bravery. His obituary in a Tokyo newspaper referred to him simply as “a former diplomat.” But to the thousands of people alive because of him, and to the millions who have since learned his name, he is something more.

Not a man of speeches. Not a man of rebellion.

Just a man who looked into the eyes of those asking for help — and chose not to follow silence.

He once said:

“I may have to disobey my government, but if I don’t, I would be disobeying God.”

And with that quiet conviction, he changed the course of countless lives.

The Echo of His Signature

There are no grand monuments built by Sugihara. No sweeping campaigns.

Just the slow, steady sound of pen on paper.

Just a family helping him fold forms late into the night.

Just a train window, and one last reach of the hand.

These aren’t dramatic images — but they’re powerful.

They remind us that even in a world broken by war, sometimes the most courageous act is to say “yes” when everyone else says “no.”

And to write a name when that name means someone gets to live.

One Comment